Happy St. Patrick’s Day! I don’t know who the parent was who started this whole leprechaun turning your toilet water green and doing silly things around the house and bringing St. Patrick’s Day presents, but I’d like to have a word… or several words with them!

As I was walking my daughter to school this morning, her friend came running up to her showing her some cheap, plastic necklace, saying “look what the leprechaun brought me!” My daughter replied, sheepishly, that the leprechaun usually brings her presents while she’s at school. Folks, the leprechaun will not be bringing presents. The leprechaun has never brought presents. Honestly, what is wrong with all of us? Parents, why do we do this to ourselves and our kids?! Are we truly this eager for any opportunity to buy even more cheap shit for our kids?

I want to talk about tourism and colonialism. There’s a way in which wealthy White people from the Global North feeling entitled to travel wherever they want around the world, especially to countries in the Global South, gives just a whiff of colonizer to me. You know what I mean?

I definitely know people for whom traveling to far-flung, “exotic” locales is a badge of honor; a kind of “look at me and all the cool places I’ve been; I’m so well-traveled” vibe.

Really, is there anything more bougie than being “well-traveled?”

And let me make it clear, I’m very much casting stones at myself here. I am - or at least, was - this person. After college, and again after law school, I traveled a lot. I racked up those stamps and visas from cool places. Japan, China, Mongolia, Tibet, India, Russia, Croatia, Argentina, Chile... I could go on. I’m doing the “look at how well-traveled I am” thing right now! I like talking about the places I’ve been! They were all amazing experiences in their own way. It was an enormous privilege to travel to those places, and I had the opportunity to learn about cultures and do and see amazing things.

But let me also be real. I didn’t develop a deep relationship to or understanding of a people or their culture or their land on those trips. Those experiences were, primarily, ones of consumption. While travel has the potential to expand horizons and shape us into more understanding, thoughtful people, it just as often is simply about consuming an experience. So much of it amounts to little more than exoticism. Like early European explorers, we land on the shores of far-off places, gawk at the locals, leave the detritus of our consumptive lives and worldviews, and often, leave these places worse than we found them.

Did my experience in Mongolia, for example, leave an indelible impression on me? Yes. Did I learn things? Absolutely. Was it in any way reciprocal or rooted in relationship-building? Nope. Unless you count the fact that the nomadic family I stayed with was paid for hosting me in their yurt. Which I don’t, because transactions and relationships aren’t the same thing.

The show White Lotus is actually a great example of what I mean about travel as a kind of extension of colonialism. A bunch of wealthy assholes travel to a country with great beaches, in an area of the world with a long history of colonialism (though, Thailand itself managed to remain independent, partly through diplomacy, acting as a buffer between British and French colonial territories), extracting the labor of the employees for their own pleasure/self-care/enjoyment, and have no real interest in the culture or people. To the extent that they engage with the culture, it’s for entertainment and consumption. The season of White Lotus that took place in Hawaii was, perhaps, an even more perfect example. It’s easy to tell ourselves that it’s a good thing to support the economy in these places through tourism. Maybe it is (though, as a PSA, Native Hawaiians don’t really want you there). But, I also can’t help but think about how much of the world has either been ravaged by colonialism, or at least suffered under Western hegemony, and is now dependent on tourism to support local economies. There’s something pretty gross about the Global North extracting colonial wealth from places, and now many of those places have developed industries around catering to wealthy tourists.

I really do have complicated feelings, though. Travel has directly contributed to my own understanding of the world and an expansion of how I think and how I empathize. I also think Americans are deeply unpracticed in internationalism, a perspective desperately needed right now. We could learn a thing or two from other countries about, oh, I don’t know, resisting authoritarians, for example, if we weren’t so entrenched in our exceptionalism.

But, I keep coming back to the question: What does ethical travel look like in a time of climate chaos, when massive systems and culture change is desperately needed, and needed the most from the people who feel most entitled to hop on a plane to wherever they want, whenever they want? I genuinely don’t know. But I feel quite confident that us privileged few need to urgently reevaluate what we think we need to live a good life, and what we think we’re entitled to.

I can’t bring myself to believe that it’s necessary to travel the world in order to live a good life, because that means a good life is inaccessible to the 6.5 billion people who will never fly in their lifetimes. I also understand that many of us who are among the wealthiest people in the world live in countries that have no social safety nets, work us to the bone, and leave us struggling to pay bills. If we manage to save for a vacation now and then, I understand why it’s hard for that to feel like some incredible, elitist privilege.

In an ideal world, billions more people would have affordable access to travel, and we’d all have ways to see and experience the world without spewing greenhouse gas emissions we simply can’t afford to spew anymore.

But, we don’t live in that world. That world is nowhere on the horizon, and wont’ be without that massive systems and culture change I was talking about.

So what do we do now, in the world we’ve actually got?

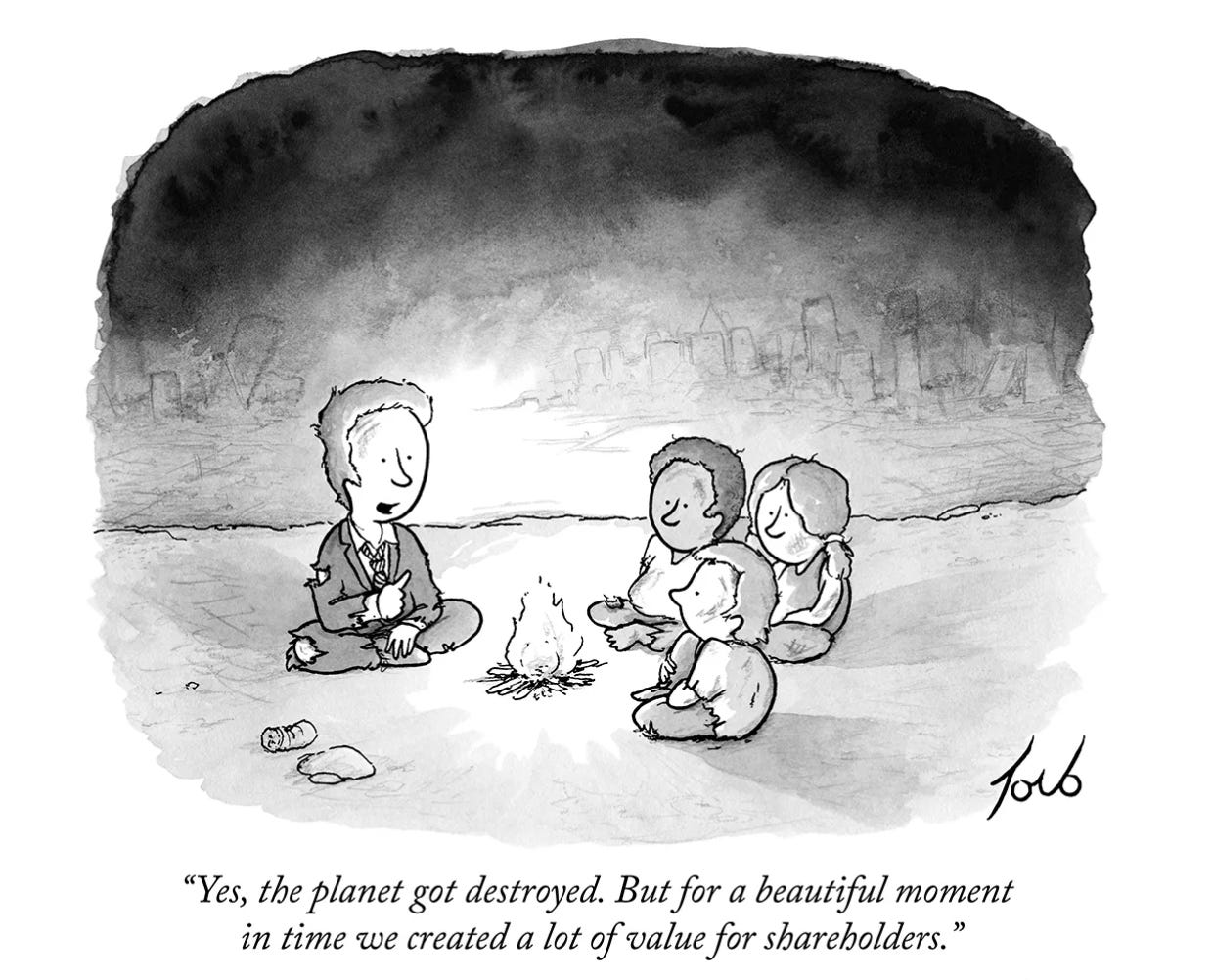

Back to the climate crisis. I’ve been working in or adjacent to the climate space for about two decades; more if you count my years as a tree-hugging teenager. I’m convinced that the reason we haven’t solved this problem is because those of us who have the most to lose won’t accept that we do, in fact, need to change how we live. It’s been taboo for quite some time in the environmental space to suggest that we do, and anyone who dares say so gets reminded that BP created the idea of the carbon footprint.

Heck, just before the Rio Summit in 1992 - the predecessor to the annual UN Climate Summits - George H.W. Bush famously declared “The American way of life is not up for negotiations. Period.” More than thirty years later, the American way of life consumes more resources than ever, and yet, is still, definitively, not up for negotiations. We simply insist somebody else figure out how to power our consumption cleanly.

This is what White, affluent environmentalism looks like.

No amount of techno-utopianism is going to save us from the consequences of a global economy predicated on infinite expansion, on a finite planet with finite resources. And yet, we cannot speak of the fact that the planet would never be able to support a world in which all 8 billion of us lived the way an average American lives.

The climate crisis is a systemic problem, and the global 1% wealthiest are the system. We shape geopolitics and the systems that underpin those relationships; we run the businesses, media companies, advertising agencies, governments, universities and NGOs - the global levers of power - and we’re the ones whose consumption drives the demand for the world’s dirtiest products and industries. Our lives are only possible because of the wealth and resource inequality that make them possible. And we’re the ones insisting on the minor, incremental changes that leave everything about our lives intact.

To expect a human-made system to change without expecting the humans who made the system to change seems like a fool’s errand, to me.

The most privileged people on this planet are willing to swap for the greener option (well, some of them, anyway) that don’t disrupt their lives: electric vehicles, induction ovens, solar panels, and maybe even fake meat instead of real meat. But ask them to relinquish the American lifestyle for something that’s genuinely more sustainable? Nope. Not negotiable.

And that’s the single biggest reason I’ve shifted my thinking from “solving” the climate crisis with nothing more than clean energy and electrification, to thinking about what it would look like to be prepared, and live a meaningful and joyful life even in the face of ever-increasing climate chaos. It’s also why I’m thinking so much about climate action as solidarity, with the billions of people whose lives and labor make my comforts and conveniences possible. I have to believe that we don’t have to live this way; but for that to be true, I have to be willing to take action aligned with my values and vision.

Truthfully, I’m not hopeful we will solve this crisis. But I am hopeful that the kind of lives we will need to live in the face of profound inequality and growing material insecurity, also happen to be the kind of lives we need to live to avert the worst of this crisis.

In other words, living in such a way that prepares us for the worst - which is to say, doing more with less - is itself a strategy to avert the worst. If enough of us do it. That’s always the rub.

I decided this was the year to take my kids to a place I love because the ecosystem there is dying and I want them to see it before it’s gone. But the reality is, the ecosystem there is dying in part because I, and people like me, have thought nothing of hopping on a plane every year to go there for a nice beach vacation, where I put on my toxic sunscreen and swim around with endangered sea turtles; colonizing the land with my trash, the sea with my chemical skin-care, and the sky with my greenhouse gas emissions.

We’re often told to live big, full lives, but that frequently seems to translate to consumption - whether it’s things or experiences - rather than meaning. We Americans, we globally wealthy, are so obsessed with the idea that bigger is better. I have to believe that there’s also beauty and fullness in the small and simple, in what we already have.

I don’t have any easy answers. But I have a hard answer, which is that, when people and the planet are in crisis because of over-consumption, it’s time for those of us who have the privilege to consume what we want, not just what we need, to rethink what constitutes a good life.

And maybe a good life means, at least in part, finding the big, beautiful magic right here in front of us.