I’m feeling a bit strapped for time this week. I’m, in fact, remembering right now that I meant to throw in load of laundry three hours ago in preparation for family visiting this weekend. Anyway, usually this results in an overly long essay because I don’t have as much time to edit. Thanks for bearing with my rambles today!

Last week I went dark. It just needed to happen. But this week, it’s all love and dreams!

I write a lot about “radical imagination.” I have a degree in creative writing, and I’ve been telling stories (mostly to myself) my whole life, so I’m no stranger to thinking about things that don’t exist. In fact, it’s one of my favorite pastimes. But I understand this doesn’t come easily to a lot of people. And it’s especially difficult for people to imagine the “real world” functioning fundamentally differently than it does now. Thus the quote, attributed to Fredric Jameson, "It is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism.”

Fortunately, we have lots of writers and thinkers who can imagine an end to capitalism (and many of the other oppressive systems we live under) and write about it, so we can get a little help with our own imaginative capacity. Lucky us!

When I talk about imagining the world functioning differently, I mean really picture it in your mind. What would it look and feel like to live in a world where everyone was housed? How would your own housing situation change? How would it change your town or city? Imagine a world where every child had access to the same resources, education, and emotional support. What are some details of how that could work? How would it change your family life? Your day to day routine as a parent? Imagine a world where our economy was not built on extraction, disposability, growth, and profit, but was solely designed to meet human need? What if we never threw anything away? It wasn’t that long ago that our ancestors lived without taking out the trash in plastic bags every week. How would grocery shopping change? Or birthday parties change? Or vacations?

You can’t bring anything into being if you can’t imagine it. We all know this, but it bears repeating, because we also seem to forget it regularly. Which is why, when I pose questions like the ones above, they’re immediately dismissed by some people as “naive” or “unrealistic” - because these people have forgotten (or never learned) how to use their imaginations. They take for granted that the way we live now is the way we must always live; or maybe they think we as a species have landed on the “best” way (conveniently ignoring the billions of people living in abject poverty and catastrophic climate breakdown, which are the direct result of the systems we’ve built).

We tend to forget that right now we’re living in someone’s imagination (namely, the imagination of wealthy, white, colonialist, imperialist men). Virtually everything about how our lives are structured - education, economy, technology, legal systems, family units, housing, cities/towns, governments, countries - it’s all made up by people. The systems we have now were created by people who, let’s be real, didn’t value all human life equally (colonialists) and who do not believe in the value of all living things and the ecosystems that support them (capitalists). But it wasn’t always like this. And it’ll no doubt change again.

For me, the movement for prison and police abolition has been my gateway into truly radical political imagination. I first heard an interview with Mariame Kaba, a leader in the abolition movement, probably about six years ago. I’ll admit, at first I was very skeptical. I had a very hard time imagining it. But, I was also curious and wanted to learn more, because I felt strongly that the system of policing and incarceration that we have now causes a level of suffering I’m not willing to accept in the name of “safety.” So, the more I read and the more I listened and learned, the more I was able to begin to picture what it could look like to have accountability without punishment and incarceration, to have safety without having to call men with guns to come and throw someone in a prison cell. I really think that it’s people’s lack of imagination that makes them terrified of abolition, and if they were willing to engage with the ideas, a lot of people would probably come around to much, if not all of it.

Some of us, myself included, would very much like to see an end to the violent death machine and failed project that is the United States as we know it. I’m tired of being told “vote blue no matter who” and that we can tweak and reform our way out of this warmongering horror show of a country. Perhaps some of you out there think it’s not that bad, or maybe the prospect of radical change is terrifying to you. But frankly, whether we like it or not, our country is in the process of a dramatic transformation, very possibly for the worse (unless you’re a fan of fascism). So those of us who share the values of equality, compassion, reciprocity with and love for the natural world, etc. damn well better be able to envision what’s on the other side of this mess we’re in, because we know for sure the far right wingers have not only envisioned it, but they’re actively coalescing around a plan that’s already being enacted.

Imagination has always come easily to me, but not necessarily political imagination, and certainly not in any real, tangible way. So I’m going to tell you about some of the writers I’m deeply grateful for, who’ve helped me start to expand my own ideas of what’s possible.

I’m going to start with adrienne maree brown. I read her book Emergent Strategy a number of years ago, and it was quite transformative. She uses the frameworks of natural cycles and patterns, as well as science fiction, to examine how to shape social change and social movements. It’s expansive, creative, and generous, and was a very new to me way of viewing the work of social change. She describes movements replicating and expanding as fractals; groups working together and tuning into each other like a murmuration of starlings; grounding our work in the natural rhythms of our bodies to avoid burnout. Now that I’m writing about it, I’m actually feeling like I need to reread this right now, as the world feels so charged and grief-filled and this book is kind of a soothing balm for me when change feels painful.

Brown frequently cites science fiction writer Octavia Butler as a strong influence of her work. I’ll admit I hadn’t read any Butler before coming across brown’s work. I wanted to see what all the fuss was about, so I read Butler’s books Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents. While these are billed as sci-fi, sadly they’re feeling more and more realistic by the day. Set in a dystopian future America (they happen to take place RIGHT NOW - in the 2020s) where climate change has ravaged the ecosystem and wealth and social inequality has ravaged society, it’s the story of how a group of people band together to survive. For me, the deep value of Butler’s work from a radical imagination perspective is about what it means to be in community with each other, and to learn to navigate love, pain, loss, and differences of opinion and perspective within a group that must learn to work together. It also, honestly, makes me feel like I need to learn how to handle a gun and field dress a deer. Basically, these stories are survival manuals, both from a material, but also a spiritual perspective.

And this brings me to the radical feminist anarchist queen of my heart, Ursula K. Le Guin. If Butler teaches us how to survive the collapse of civilization as we know it, Le Guin teaches us how to imagine what could be on the other side. Her novel, The Dispossessed, has probably done more than any other work I’ve read to help me envision a world beyond capitalism, exploitation, and inequality. What I liked about the “utopian” world she creates in this book, Anarres, is that it’s still imperfect. There’s a tension between collectivism and individualism; there are downsides to the egalitarianism of the anarcho-syndicalist society she’s envisioned. All of which is to say, it feels real. She explores this society in enough detail and nuance that it was the first time I could ever palpably imagine how a radically collectivist and largely non-hierarchical society could work. She takes political theory and makes it “lived in.”

I can’t leave a conversation about Le Guin without also mentioning another work that has deeply influenced my own radical imagination: The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. This essay subverts the usual story of human progress focused on the development of technologies of domination: the weapons heroes wield to conquer lands and vanquish enemies, and instead argues that the most important human technology was the lowly container. Le Guin argues that the vessels of human culture, whether a basket to hold foraged foods, a net to catch fish, or the homes and shrines we build to protect our most sacred things - ourselves and our dreams - are the true seeds of human development. What a soft and generous view of our collective origin story. Le Guin had such a gift for seeing the world with such depth, and for refusing to allow “reality” to fix her imagination. And so, of course, she is also the utterer of some of my favorite words to ever be uttered by a writer:

“We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.”

And this is, to me, the crux of radical imagination. The ability to recognize the mutability and malleability of so much of what we deem “reality,” and the essential role of art and creativity in shaping and reshaping our world.

Lastly, I want to end with the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer, specifically, Braiding Sweetgrass. I’ve written about this book before; I tell everyone to read it. I will admit, it feels like her work has become very popular amongst a certain subset of white ladies who care about the planet. So, I always feel self-conscious being such a fangirl. But she just so beautifully illustrates what it could look like to live in right relationship with the earth. If you’re not yet ready to dive into the book, I recommend reading her essay, The Serviceberry, which touches on many of the same themes of Braiding Sweetgrass, like reimagining (or, in fact, remembering) our place within our ecosystem, that people and land and “economies” can’t prosper if our relationships are based on taking alone. We need reciprocity to ensure abundance and sustainability. “All flourishing is mutual,” she says. I mean, whew! What a basic and yet revolutionary idea in our western, colonialist world!

Letting our imaginations spill beyond the containers of our current material and cultural reality can be hard, even for those of us fairly well-versed in make-believe. Fortunately, imagination is a muscle, and the more you read, watch, listen, and explore, the more you exercise it and the bigger it gets. And the more you can imagine the world you want to build, the less scary uncertainty and change become.

As Toni Morrison instructed us: “Dream a little before you think.”

Postscript:

Shout outs to Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline and the economic degrowth movement for specifically stretching my radical environmental imagination. The environmental movement is still so stodgy and white and free market focused, and um, unfortunately we don’t have time for that shit anymore.

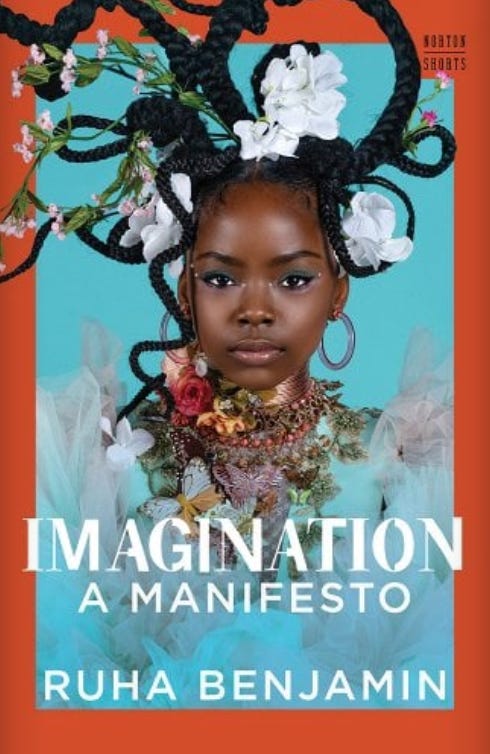

Also, earlier this week, as I was starting to write this, I saw that Ruha Benjamin came out with a new book called Imagination: A Manifesto. What?! Yes, please! Also, it has, hands down, the most beautiful book cover I’ve EVER seen. Later this afternoon I’m headed over to my local bookstore to pick it up. Anyone up for a book club discussion?